Negotiating New Terms and Conditions

By Junia Howell | May 20, 2025

3 minute read

Over the last decade, user agreements have become a weekly activity. Downloading a new app, setting up a new online account, or purchasing an item through a virtual store, the user is asked to check a box indicating that they will comply with the hyperlinked terms and conditions.

I used to feel compelled to read every word of these agreements, but lately I’ve taken another tack—checking the box without even laying eyes on the contract. To me, this approach felt new, a byproduct of the ubiquity of these contracts. But I recently realized it isn’t new at all.

Old Wine, New Wineskins

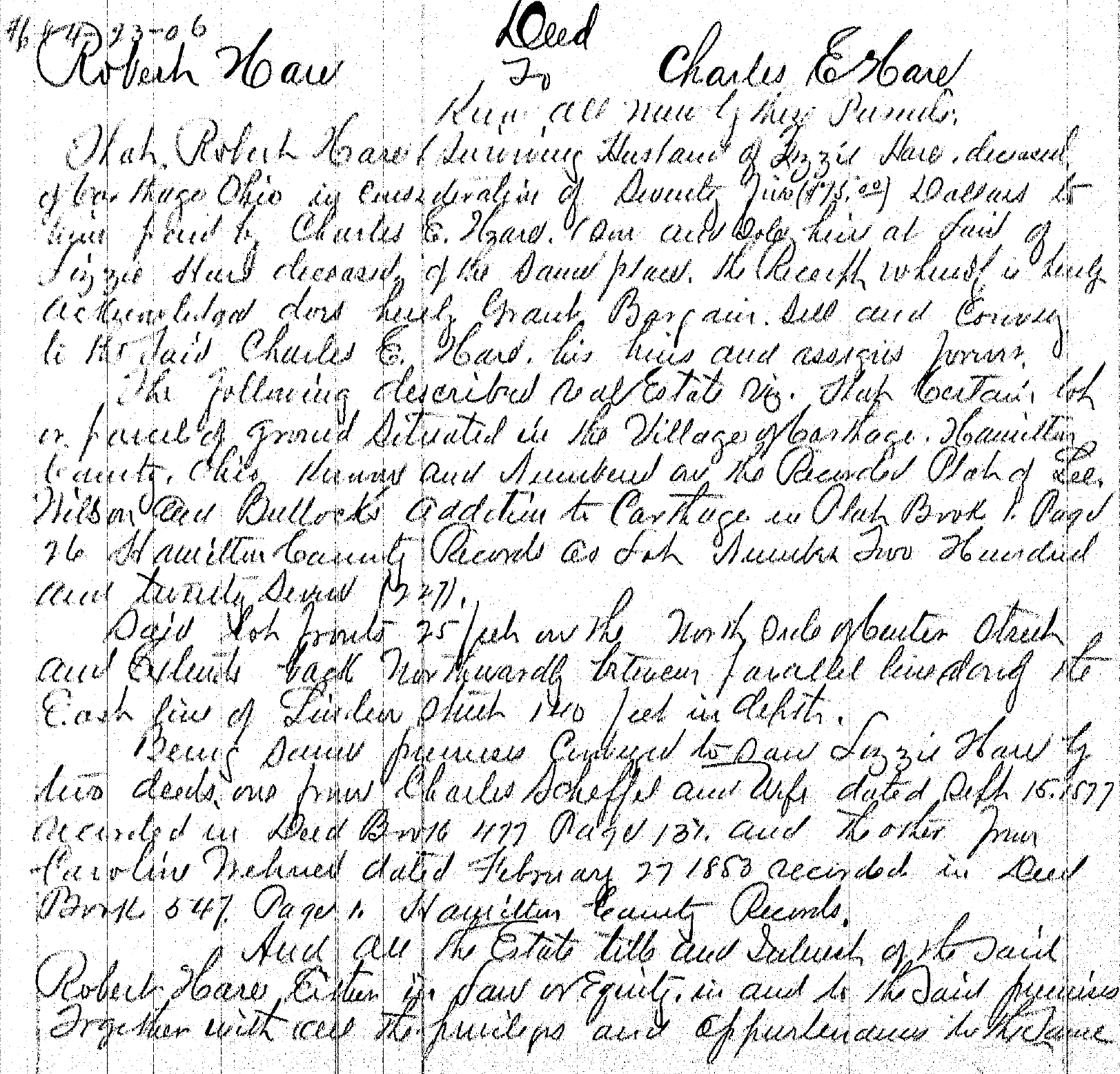

Lately, I’ve been studying a series of historical property deeds from the mid-1900s back to the 1700s. Deeds are relatively short. Most are only a page. A starling brevity considering deeds are the only legal documentation verifying the ownership of most people’s largest asset.

Like contemporary user agreements that merely hyperlink to the full list of terms and conditions, deeds contain minimal details. The long list of rules and requirements that accompany property ownership are merely referenced in passing. To access all the critical details, a buyer must consult the municipality’s property laws.

Much like their virtual counterparts, few buyers take the time to look up all the local property laws. Rather they assume they understand the basic tenets of ownership. Property owners simply check the metaphorical box.

Figure 1. Historical Deed

Ownership, An Alterable User Agreement

This comparison made an impression on me. I suddenly realized property ownership is much easier to comprehend if framed as a user agreement.

It's an agreement with a local government. A user can continue to access the specified property as long as they comply with all local laws, including paying annual property taxes.

But the local government can alter the user agreements, including property taxes, as long as the elected officials or local electorate agree that the new terms are best for the collective community. We engage in this process all the time, yet rarely do we fully consider the extent to which we could fundamentally rethink the terms.

Taxing Basic Needs

Over the past two years, I have done multiple studies on property tax. The most recent is a study I am conducting as part of the Boston Federal Reserve Visiting Scholars program, looking into how much residents pay in property tax relative to their wealth.

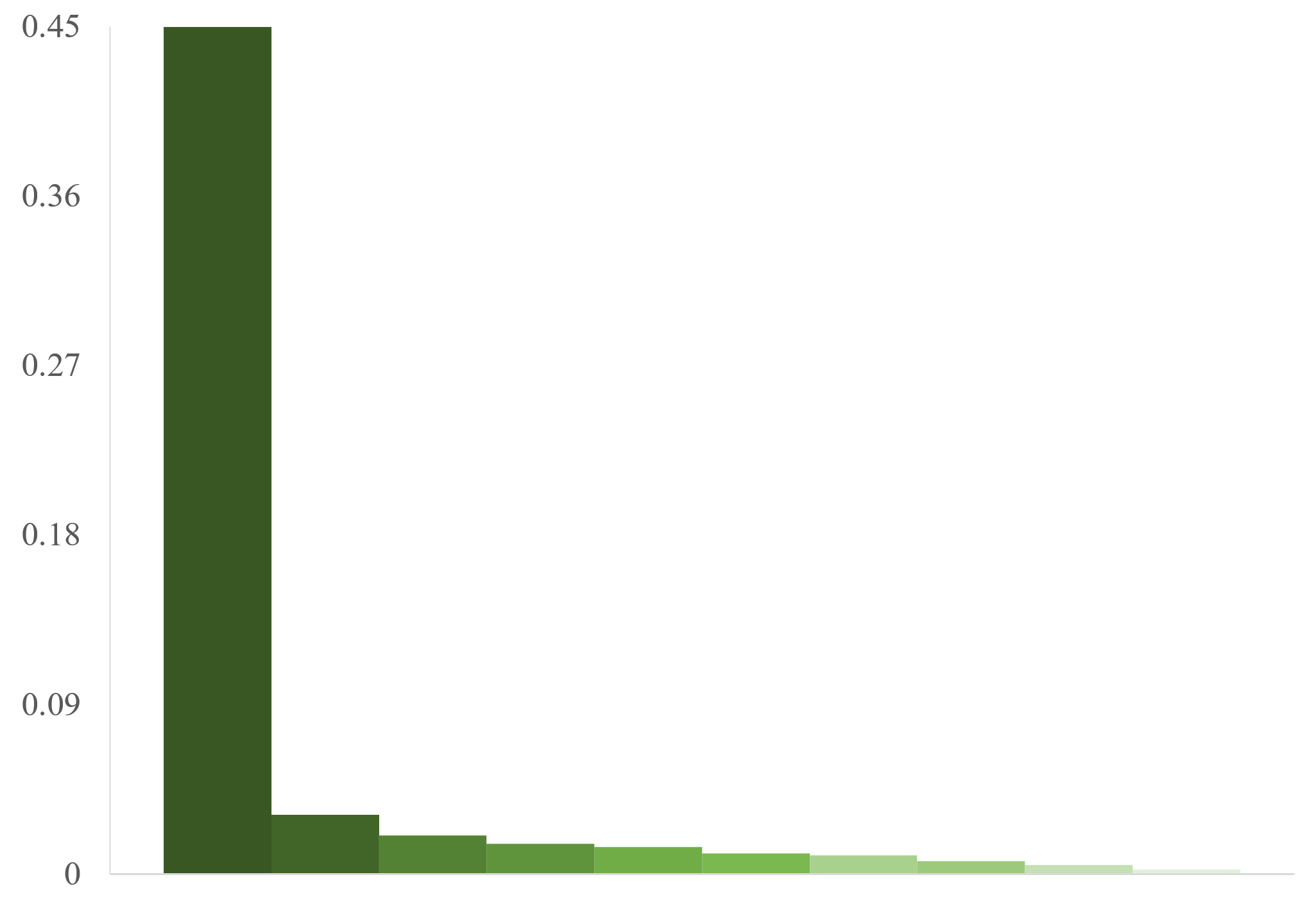

Homeowners whose net worth is in the bottom 10% pay 45% of their net worth in annual property taxes. Most of their net worth is in the value of their property, which isn’t liquid cash. This means that each year they are spending substantial proportions of their annual income on property taxes.

Conversely, those whose net worth is in the top 10% of the wealth distribution spend not even a third of 1% of their wealth on property tax. It also often corresponds with a much smaller percentage of their annual income. Moreover, these inequalities have increased over time.

Figure 2. Homeowners Mean Proportion of Net Worth Spent on Annual Property Tax by Net

Worth Decile, 2021

Likewise, homeowners who make more money over time from their properties’ appreciation spend a smaller proportion of their gained wealth on property taxes.

We often call property tax a wealth tax, but when we look at actual measures of wealth, we find property tax is not equally levied across residents’ wealth. Instead, those with the fewest resources pay the most.

This is particularly problematic when we consider that housing is a basic need. For other basic needs, like groceries, most governments prohibit taxation because of the undue burden that puts on the poor. The data shows that the poor also disproportionately carry the burden of property taxation.

A New Agreement

Local governments’ current approaches for approximating property values do not reflect residents’ wealth or how much they accumulate from their properties’ appreciation. If we are really interested in taxing wealth, local governments should consider taxing capital gains—annual profits from financial investments. This would ensure more equitable taxation and reduce housing costs for the vast majority of residents.

This is not out of reach. We have malleable user agreements between local governments and their residents. The terms and conditions of home ownership can be changed in favor of equity. We merely need to recognize the possibilities.